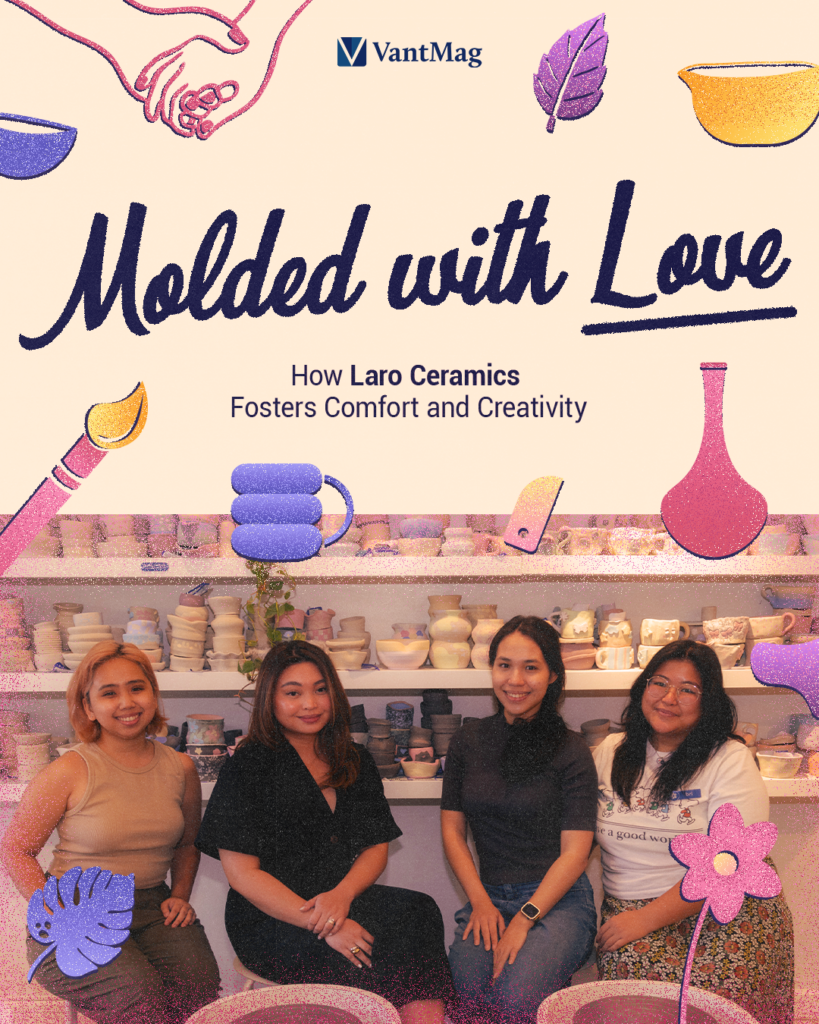

What turns moments into milestones? For Agnes Arellano, her journey through womanhood and motherhood shines brightest in hindsight. Located at the Ignacio B. Gimenez Amphitheater of Ateneo de Manila University’s Areté, the sculpture installation Inscapes: A Retrospective unpacks her personal history and celebrates 36 years of artistry.

In this feature, three Ateneans were interviewed to read into Arellano’s work: Department of Philosophy Associate Professor Remmon Barbaza, PhD, Leila Ramirez (3 AB IS, Psychology and Communications tracks), an avid reader on abstract and conceptual art, and Joaquin Opulencia (3 AB IS, Information Design and Management tracks), a film photography enthusiast.

Within and without

The term “inscape,” a combination of interior and landscape, can be viewed as a terrain of one’s self. Arellano’s psyche is represented in a collection of 16 sculptures shaped and casted from her own body. In Inscapes, her life can be seen as one picture in a panoramic, semi-circle arrangement.

Opulencia compares this to photographed landscapes that form a coherent image as many elements simultaneously come into play. He explains that “as one draws closer to zoom into each sculpture, a specific point in her [Arellano’s] life is discovered.” For Barbaza, the layout encourages the audience to engage with the sculptures. “It’s like the installation is asking me as a viewer to not just look at it from a distance but to get close,” he says.

The sculptures’ lack of color is another inviting feature of the installation. Opulencia notes that this quality gives greater room for interpretation. “Once you add [more] color,” he adds, “it imposes and adds another dimension to the piece.” Their fading finish also indicates temporality and transience–themes ever-present throughout the exhibit. And among these sculptures, there were three particular pieces of interest.

Yabyum

“Yabyum,” the Tibetan term for father-mother, is an image of man and woman in erotic embrace. In Himalayan Buddhist imagery, this symbolizes the unity of compassion and wisdom: The two most important forces in the universe for achieving harmony and enlightenment.

With this, Ramirez sees Yabyum as a statement of how a woman’s sexual energy need not be repressed as man and woman become one. “Man and woman are supposed to be equal and one in this whole journey towards this ‘cosmic consciousness,’” she says. “But it hasn’t been that way in the world.”

Barbaza calls the whole installation a “drama of life and death” as played out by two actors: Man and woman in a loving struggle as equals. He draws focus to Yabyum’s depiction of man and woman as equals. “Neither dominates the other,” he concludes. “One is not dominated nor overwhelmed.”

Obelisk

The Obelisk is a monument of death made from densely merged skulls and bones–erected as a reminder of the catacombs in Rome, Ifugao burial caves, and extrajudicial killings. Opulencia takes Arellano’s portrayal of Obelisk as an evaluation of civilization. Pillars and edifices are put up from left to right, but despite their initial magnificence, they beg the question: At what expense were these structures put up? Obelisk is then reflective of society’s external glamor, which can be full of monuments that have compromised and sacrificed actual human lives.

Similarly, Barbaza notes the connections between life and death in the Obelisk. “[In these tensions,] there is wonder and praise for our life-giving capacities,” he explains. “There is also shame and guilt in the same breadth—in our ability to destroy, cause harm, and bring about death.” By confronting this glamour and gore, beauty and bloodshed, the Obelisk stands to face humanity with the price of its actions.

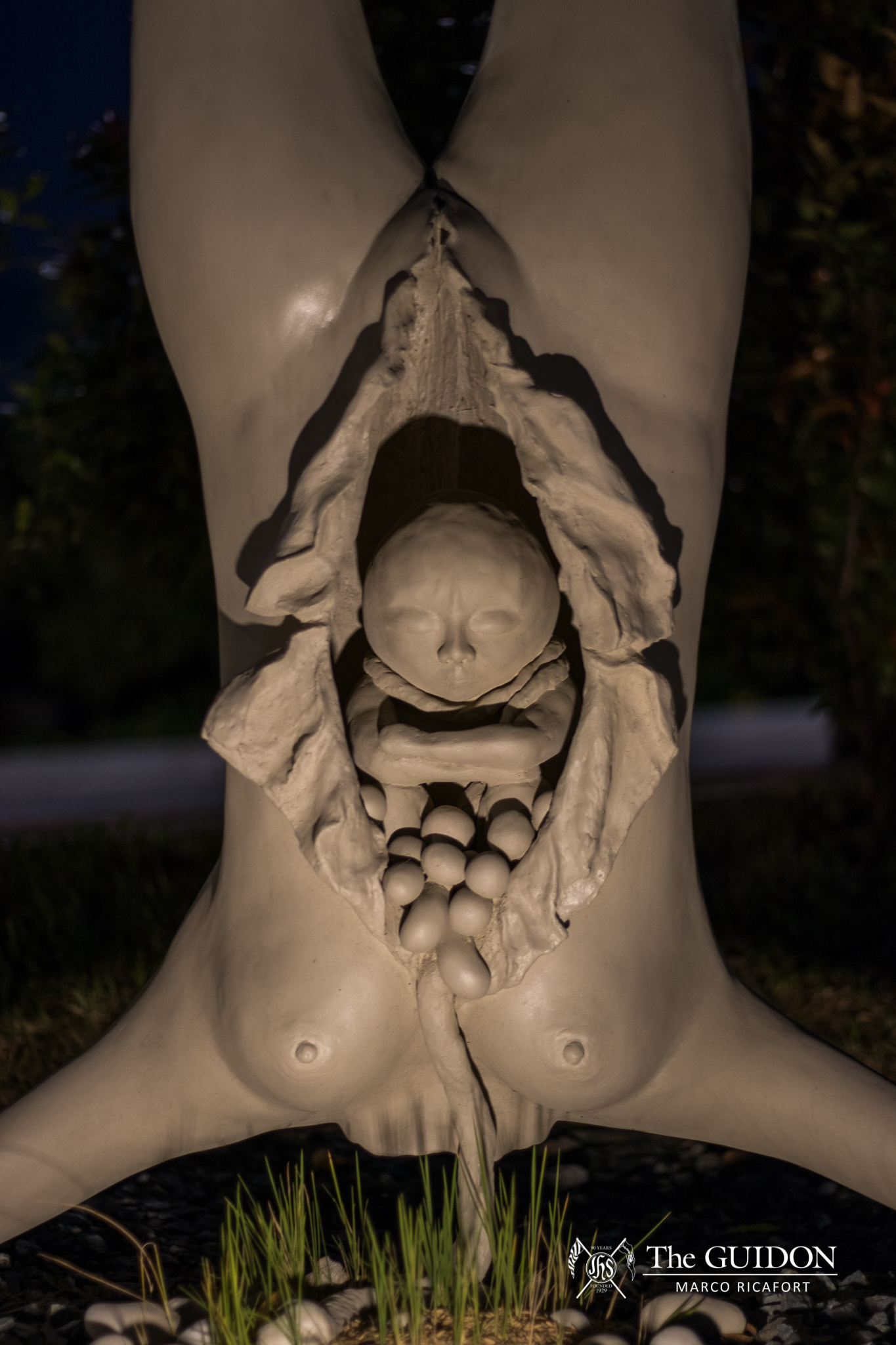

Carcass Cornucopia

Carcass Cornucopia visualizes how new life can spring from destruction. With the female abdomen slashed, the bounty of the universe spills out–depicted as a serpent swimming in a mound of unhusked rice, while a miniature bulol (i.e., Philippine harvest god) remains in the female bovine’s hollow cadaver.

The irony of the name is a notable dichotomy for Opulencia: A carcass, a cut-up piece of dead meat, grants a sacred abundance that is cornucopia. He adds that while pregnancy is the signifier of life for most of the installation, Carcass Cornucopia shifts this representation to the lacerated body instead. The installation demonstrates how, from the progression of pregnancy to final slaughter, life still remains.

Ramirez finds that the reflective aspect of Carcass Cornucopia echoes the words of philosopher Allan Watts: “You are the universe experiencing itself.” From Arellano’s description of the sculpture as a “bounty of the universe spilling out,” Watts’ philosophy comes into play as the acknowledgement of the infinite world working within her–even with the patriarchy’s stifling of this universe.

All this considered, Inscapes disturbs with liberated, explicit imagery, as it gives voice to both sexuality and spirituality. Here, Arellano communicates an independent yet universal history. Her craft reveals the deepest faculties of her spirit, authenticated by every moment of healing and illness, love and loss undergone as a woman and mother. Inscapes entirely is a place of enlightenment: A realization that looking beyond can only be done by first looking within.

Editors’ Note: Some information here about the sculptor was sourced from the artist’s website and the exhibit pamphlet. Agnes Arellano’s Inscapes: A Retrospective will be on display until March 15, 2020.