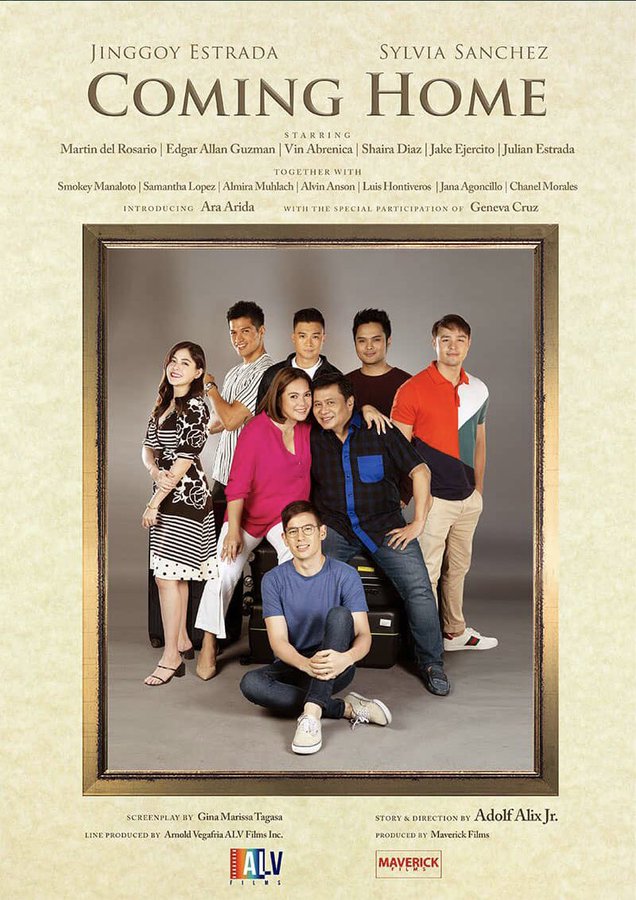

Originally slated to premiere at the Metro Manila Summer Film Festival in early 2020, Adolfo Alix Jr.’s family drama Coming Home is an aptly-themed film for the holidays. However, the film’s formula is structurally Swiss cheese-like: Fairly digestible but not without its share of holes.

At the heart of the film is the Librada family. Benny (Jinggoy Estrada), is an overseas Filipino worker (OFW) in Qatar while his wife Salve (Sylvia Sanchez) is a homemaker who stays in the Philippines. She tends to their six children: Berns (Julian Estrada), Ned (Edgar Allan Guzman), Enji (Jake Ejercito), SJ (Vin Abrenica), Yuri (Martin del Rosario), and Sally (Shaira Diaz). After 10 years, Benny comes home, excess baggage in tow.

In Qatar, Benny meets Mercy (Ariella Arida), a fellow OFW who becomes his mistress. They are entangled through Benny’s desire to help Mercy with a debt, compromising his family’s own financial needs back home. As the children grow older in Benny’s decade-long absence, they find themselves in predicaments parallel to Benny and Salve’s. The children become paramours, leave home for work, and blindly accept partners despite their abusiveness.

Although some satisfaction can be found in the resolution of the children’s individual problems, a lingering lack of actionability on the film’s greater conflicts spoils it. Accountability is passed around like a game of hot potato; the wronged characters find themselves bending over backwards to accommodate the wrongdoing characters who went on to walk away scot-free.

Additionally, while the film touches on how globalization affects Filipino families (with three main characters being OFWs), it could’ve expounded on this with more depth and nuance.

As for the acting, much of it was believable but not as immersive as Sanchez’s. She manages to tug at heartstrings during key points of the film as the martyr-like mother of the family. In addition to Sanchez, Diaz and Guzman, who portrayed two of the children most affected by Benny’s shortfalls, gave particularly heartfelt performances.

However, the film leaves a bevy of unanswered questions at its close. What compelled Benny to come—or be brought—home after a decade-long absence? Why is Berns so unshakably attached and defensive of his father? Why are there so many Ejercito-Estradas in this film? (The last question, of course, is hypothetical.)

After two hours punctuated by face slaps, fight scenes, and an eight-minute tracking shot stuffed in the middle (likely a valiant attempt to impress), Coming Home arrives at its unsatisfying, unsustainable resolution: Acceptance no matter what because, according to the film, life is short. Yes, life can be short, unpredictable, and sometimes ruthless, but genuine healing takes time.

After failing to value-add despite being well-intentioned, Coming Home truly could have taken the longer way home.