Everyone loves a good scary movie, and ever since the invention of cinema in the 1890s, there have been filmmakers pushing the envelope on the horror film genre. From the startling (at the time) sight of a train hurtling straight towards the audience—as the Lumiere brothers put to film in their 1896 work Train Pulling Into a Station—to the modern gore-fests and shockers that litter today’s horror movie landscape, the art of terrorizing moviegoers has come a long way, and has branched out and evolved to include a multitude of subgenres and even sub-subgenres.

As cinema has grown from a largely Hollywood-centric industry to a global art form, different film industries all over the world have given their own take on the horror film genre, fusing well-established tropes with their own distinct cinematic traditions. In the broadest sense, however, the modern horror film canon may be divided into two perspectives: The West and the East.

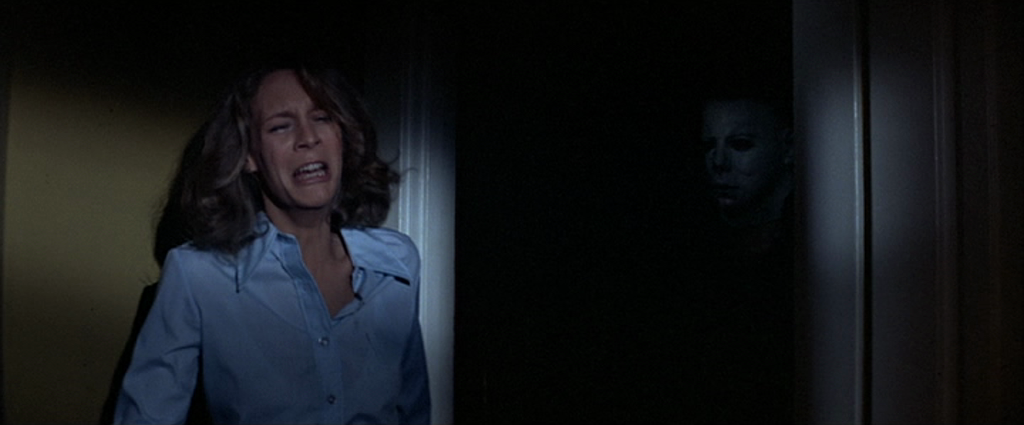

Photo from film-grab.com

Hollywood horror

While the Americans weren’t the first people to make iconic horror movies, they were the ones who codified the themes and tropes every horror filmmaker has used ever since. In fact, even the term “horror” was only used to describe the genre after Universal Studios had released Dracula (1931) and Frankenstein (1931), turning the genre from an art-house curiosity to a bankable commodity. These two films kick-started the studio’s seminal run of Gothic horror movies, which also include films like The Mummy (1932), The Invisible Man (1933), and The Wolf Man (1941). This film series set the tone for the genre at the time, with production companies such as MGM, Paramount, and RKO releasing monster movies of their own.

As technology and society moved forward, several new branches of Hollywood horror emerged. George Romero’s The Night of the Living Dead (1968) and its resulting sequels cemented a legacy of Hollywood zombie films that persists to this day, with films like 28 Days Later (2002) and TV shows like The Walking Dead still proving to be popular and culturally resonant today. Films like Psycho (1960) and Halloween (1978), meanwhile, helped usher in another staple genre in American horror—the slasher movie. These films—which tackled uniquely American themes and were not adapted from European literature like many of the monsters featured in the Universal cycle—laid the groundwork for the idea of “Hollywood horror” as a distinctly American genre.

Perhaps the most striking trend of American horror cinema after the monster movies of the ‘30s and ‘40s is its noticeable trend towards ordinary people in extraordinary situations. Films such as The Last House on the Left (1972) and Poltergeist (1982) are centered on suburban families, and feature motifs traditionally associated with domestic life being twisted and distorted into something alien. Even films such as The Exorcist (1973), which heavily uses supernatural elements, are dependent on the idea of expelling a foreign being or invader disrupting the normalcy of the film’s world.

“American horror certainly thrives on the ordinary that is suddenly made horrific,” Andrew Ty, an instructor of the Communications Department specializing in film and media studies notes, “American horror does not start from exotic places—nothing showy. It starts from the ordinary, and proceeds to have that ordinary invaded by something strange.”

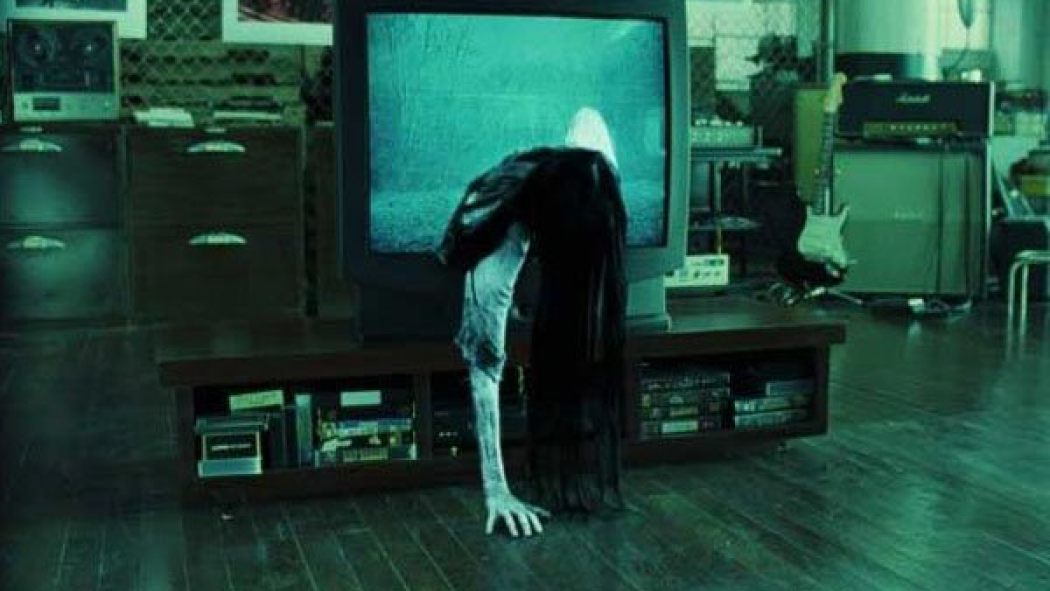

Photo from s3.birthmoviesdeath.com

Asian horror

In stark contrast to American cinema, which largely identifies the supernatural as abnormal and horrific, Asian cinema generally regards the supernatural as a normal and even crucial part of everyday life. Most horror films that come from the region generally exhibit heavy spiritual themes, and are influenced by the mythologies and legends of the countries that produce them.

Several Asian horror film traditions are rooted in pre-cinematic performance types. For instance, much of the themes and tropes found in Japanese and Chinese horror can be traced back to the Japanese kaidan, which are local folktales involving ghosts and other supernatural elements. Themes like vengeance and karma were instrumental in these narratives, which often featured an Onryō—a vengeful spirit—exacting revenge for injustices done to them in life. While this vendetta tended to target only the guilty party, it sometimes extended to all of humanity, typically manifesting itself in the form of cursed objects. This tradition informs Asian horror films like The Ring and The Grudge, where vengeance and inherited curses play a critical role.

Perhaps the most acclaimed and popular subcategory of Asian horror is the Japanese horror canon. Films such as The Ring and Dark Water have found sizable audiences on the international stage, while still remaining quintessentially Asian in the way they approach the supernatural. For instance, the original Japanese version of The Ring features a psychic character, whose abilities are simply treated as a matter of fact, and are not questioned or explained in the film. This point was written out in the American remake, which underlines the difference between the more psychological Western school of horror and its more spiritual Eastern counterpart.

“In Japanese horror, sometimes psychological motivation is not there,” Ty comments.

Photo from i1.wp.com

Bridging the gap

Funnily enough, these two differing perspectives on horror find common ground in our local horror film tradition. Films such as Feng Shui and Sukob—two wildly popular and iconic entries in the Filipino scary movie canon—make heavy use of elements taken from local superstitions and myths, but viewed through a decidedly contemporary lens. The main characters in local horror movies tend to be very modern and rational, which leaves them vulnerable when faced with the unfamiliar and the unexplainable. In a sense, a Filipino horror movie consists of Hollywood characters lost in an Asian context.

This meeting of East and West is what makes Filipino horror unique, in that it depicts characters that are detached from their spiritual or traditional roots. Like Hollywood horror cinema, Filipino scary movies are often centered on modern, domestic characters that are faced with the abnormal or the supernatural. However, these foreign elements often find their roots in ancient Filipino culture and lore, which is reminiscent of other Asian horror traditions. Thus, they aren’t really foreign; they’ve just been forgotten. It is this forgetting that is the crux of Filipino horror, and every local horror film concerns itself with bridging the gap between what we as a culture know and what we have forgotten.

As the horror genre continues to develop, new subgenres and traditions will continue to emerge, to account for changing societies and cultures. Each culture offers its own distinct brand of fear, and these fears evolve along with the rest of their societies. While the gap between Eastern and Western horror may always persist, the feeling of horror is something that is universal, because, regardless of where it comes from, everyone loves a good scary movie.