As the much-awaited “-ber” months arrive, the Philippines launches its nationwide celebration of the well-loved Yuletide season. Filipinos take celebrating Christmas to a whole new level, as we’re one of the earliest countries to start observing the holidays. While most of us back home busy ourselves with making last minute touches to Noche Buena, frenzying over last-minute shopping, and rushing to simbang gabi—a few Filipinos steadily grind and toil outside the country, miles away from home.

Overseas Filipino Workers (OFWs) make up a huge chunk of our population: There are an estimated 2.3 million overseas workers scattered across the globe as of September 2017. As a group, OFWs comprise a major sector of society that keeps the economy running. Beyond their fiscal contributions, OFWs have been attached to images of sacrifice, both for their families and for their country.

In traditional Filipino culture, the holidays are typically dedicated to maximizing time with family. In this case, what happens when family members are on far-ends of the map?

Life at home

OFW families lead very different lives compared to regular households. NGOs estimate that there are around nine million children in the Philippines living away from one or both migrant parents, and studies show that adults who grew up from these OFW families tend to recall that their childhood was greatly shaped by the fact that their parents were working abroad.

Children of overseas Filipino workers (OFWs) are said to find it difficult to manage the ever-changing modes of their lifestyle, from the sudden influx and outflow of resources entering the family coffers, to unannounced absences and arrivals of a key household member.

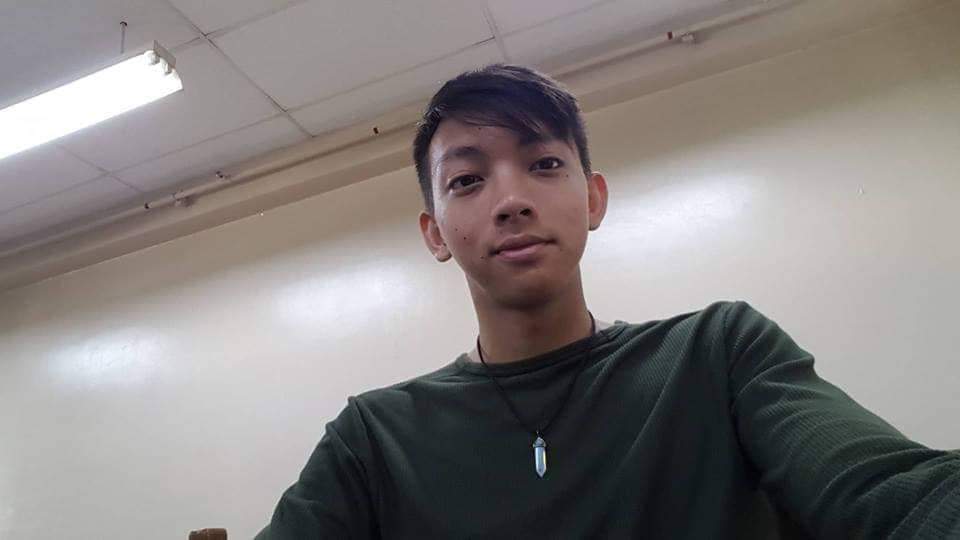

Putting a face to these statistics is 20-year old Diether Arias (2 AB EC) who has been away from his family this past year due to his parents working abroad. His father works for a motor company in Dubai, where his mother also stays.

Arias recounts moving around countries at the tender age of four. Traveling back and forth to see his parents is a standard procedure in his household. “I had to get used to it, since last year. I think that was the first time I was apart from my family, for about fourteen years,” he says. It is his first time in Manila after living in Shanghai, and even before then, they’ve moved around a few countries since.

Courtesy of Deither Arias

Courtesy of Deither Arias

But not all OFW children are accustomed to traveling frequently. Such is the case for Ager Lee Pardilla (2 AB EC), who grew up in Thailand with his mother. Pardilla recently moved to Manila to study in college, and now sees her only around twice a year.

“The distance changed me for the better of my family because I used to dislike being with my family [since] I wanted to be out more with my friends,” Pardilla admits. Now, he puts up a great effort to keep in touch with both his father and mother, who are away.

Pardilla’s set-up with his mother revolves heavily around online communication. “For us, it’s more of a spontaneous thing between me and my mom,” he says. “She just asks me how I am or how everything is going.” Pardilla’s mom finds ways to show care outside of online communication, such as occasionally sending care packages containing spare eyeglasses, candies, and food from Thailand.

Meanwhile, Pardilla’s father, a professor in Visayas, is able to visit him more often, even though he is usually unable to spend Christmas with them. When he’s in town, the two make the most of it by going to dinner and spending as much time as they can with each other.

Courtesy of Ager Lee Pardilla

Courtesy of Ager Lee Pardilla

On the perspective of the parents, the struggle lies with trying to nurture their children from a distance. In particular, mothers feel the responsibility for the emotional security of their children after migration.

For example, Mariam Moulic, who works as a flight attendant for Cathay Pacific Airways, is a proud mother of four. As a flight purser (or a head flight stewardess), she flies internationally and is away from her family for days on end.

“For me, especially as a wife and mother, the most difficult part of working abroad is being away from your family and loved ones,” Moulic says. “It [is] also very difficult when I [have] to miss important events in my children’s lives like birthdays, Christmas, school activities–especially when they would play a big role in a play or a dance or any other competition.”

She adds that it’s the feeling of helplessness that adds to the challenges of being an OFW parent. “Not being able to be there for them… Wanting to be there for them, but [you] just can’t.”

Courtesy of Mikhail Moulic

Courtesy of Mikhail Moulic

Holiday situation

The dynamic of these OFW families function much differently from regular ones—from the everyday grind of life to more special occasions, like holidays.

Pardilla and his mother usually meet at Christmas. However, increasingly demanding schedules and growing airline prices mean the family is unable to meet as often as they used to. Instead, they choose to video-call each other as much as their schedules and time differences permit.

“I think communication [is] important, but it’s a bit ironic for me since I don’t communicate with them that much,” Pardilla shares. “[The communication] gives you the boost to last until when you see them again,” he explains.

Feeling less festive without his family, Pardilla is often asked by his mother to spend Christmas with other relatives. However, he usually chooses to celebrate Christmas with his friends at his dorm.

Without his parents present, Pardilla chooses to focus his attention on his surroundings and the people around him instead. Meaningful experiences can be had with both friends and family, as he says, to “be absorbed by where you are as well, focus on the hobbies that you have and then enjoy the experiences that you can get here. ”

As such, Christmas day is spent with hanging out and playing games with friends. “I live in a dorm, so I get to see my friends really often. It’s quite easy to hang out with each other since they don’t really go home,” he explains. Although to some, this might seem to be a great Christmas experience, this is not completely the case for Pardilla. Without his parents around, the holidays lost some of their charm, he admits. “[This year’s Christmas] felt like [it] wasn’t anything special when I didn’t celebrate with them. [It was] just another day.”

Testing the tides

Studies show that Filipino families are known to be closely-knit and cohesive, but with the OFW phenomenon, however, there come challenges that affect parent-child relationships. Filipino transnational families undergo psychological and emotional challenges that affect their relationships because all members experience the pain of family separation.

From physical distance, daylight savings time, and conflicting schedules—there are numerous factors that these families have to maneuver around.

On the other hand, Arias sees how his independence has also come with an abundance of lessons. “[The] moment you depart from [your parents] and start living independently is when you see how you are as a person.” says Arias, who had to get used to doing household chores by himself, and essentially, learn how to live on his own.

“At first it was difficult, [but] the way [my parents] taught me made it less challenging for me to [be apart] from them. But I’d say that it was a learning experience—trying to figure out how to do everything myself.”

Courtesy of Deither Arias

Closing the distance has also come with a bigger effort to strengthen familial bonds. “From when I was living with them back in high school, compared to now, I think I’ve gotten closer to them,” says Arias on his relationship with his family.

Growing up in Thailand with a Pinay mother, Pardilla was closely intertwined with both Thai and Filipino culture. “It’s strange [because] when you grow up, we value, Filipinos value Christmas really highly as family time. It’s always been that way for me, and when I first spent it alone, I did find it weird,” he says.

Like with Arias, Pardilla believes the distance between his family members brought them closer together. Although he enjoyed the company of his friends in Thailand, after moving to the Philippines, Pardilla found his outlook changed. “Now that I’m here and staying alone, I have started to appreciate being with my mother more, so if she comes, I try to spend as much time with her as possible.”

Courtesy of Ager Lee Pardilla

Courtesy of Ager Lee Pardilla

The decision to work away from the family has been found to reap both favorable and unfavorable consequences. In a study by the University of Mindanao, financial stability is one of the obvious benefits, but emotionally, there also involves the “feeling of emptiness and lost time to be close with one another.” The same study explains that more importantly, aside from investing their earnings in something economically viable, family members do try to “hold on to their family values as much as possible through constant communication and care for each other.”

Come hell or high water

Fixating on the obstacles that come with living away from home is not an option for these families. OFWs and their children take the extra mile to keep in touch, and these families share exactly how they rise up to the challenge.

Nowadays, it’s much easier to stay in contact, given the aid of technology. “During the early years of my work I would usually call every once in a while using ‘Magic Jack’ (a phone service allowing overseas calls before online communication became popular) but now it’s a lot easier to keep in touch with them with the help of Viber, Facebook Messenger, and Facetime,” says Moulic. “When I am home with them, I try my best to go out with them. [Now] that they’re older, there are times they’re the ones that ask me out to movie dates and [lunches].”

Moulic also stresses the need to compensate when she is physically with her family. “I would like to think that because of the times I was away, I [make] sure I [am] there for them,” she says. “I try my best to plan in advanced days wherein I could take a leave or days off from work and save these opportunities for when my children have special events, like graduations.”

Courtesy of Mikhail Moulic

Courtesy of Mikhail Moulic

Pardilla, when given the chance to chat with his mother, will check in on everything happening back home. “I ask her what’s been going around in our village where we live and [if] anything [has] changed,” he says. “I ask how our pets are doing: our fish, our dog, and our cat. I ask her if there’s any changes to nearby restaurants because I love the food there.”

For Arias, his advice is to make the best of the situation. “Treat your independence with responsibility. You know for a fact that you are more independent now that your parents aren’t with you,” Arias says. “Also, stay in contact with [your family] every so often. Even though they don’t say it, they miss you.”

Despite the many hurdles that come with far-flung family members, distance doesn’t get in the way of sharing the holiday cheer. As Arias endearingly puts it: “We cherish our moments when we are together. The little things we do, becomes more of a bigger thing because you don’t usually get to do that when you’re not together.”

Featured Photo by Jerry Feng