THERE IS power in the written word, and poems are a particularly potent form of it. For too long, Filipinos have become victims to the injustices of the powerful.

Thus, in a show of resistance, poems of dissent have been present throughout the different regimes in Philippine politics. Here are five pieces that attempt to articulate the horrors of tyranny, published across different points in history.

Prometheus Unbound by Jose F. Lacaba

If you know any Filipino protest poem, chances are it’s this one. Due to its hidden meaning, the poem must be read in its entirety. But here is a powerful excerpt:

Hold fast to the gift of fire!

I am rage! I am wrath! I am ire!

The vulture sits on my rock,

Licks at the chains that mock

Emancipation’s breath,

Reeks of death, death, death.

On the surface level, the piece is based on the Ancient Greek trilogy of plays called Prometheia, where the Greek god Zeus’ tyranny keeps the titan Prometheus imprisoned. By taking a closer look at the poem—and considering it was published during Martial Law—one would realize it’s actually a demand for an uprising against the reign of terror. This is made clear when looking at the first letter of each line, spelling out the phrase and now-familiar rallying call, “MARCOS HITLER DIKTADOR TUTA.”

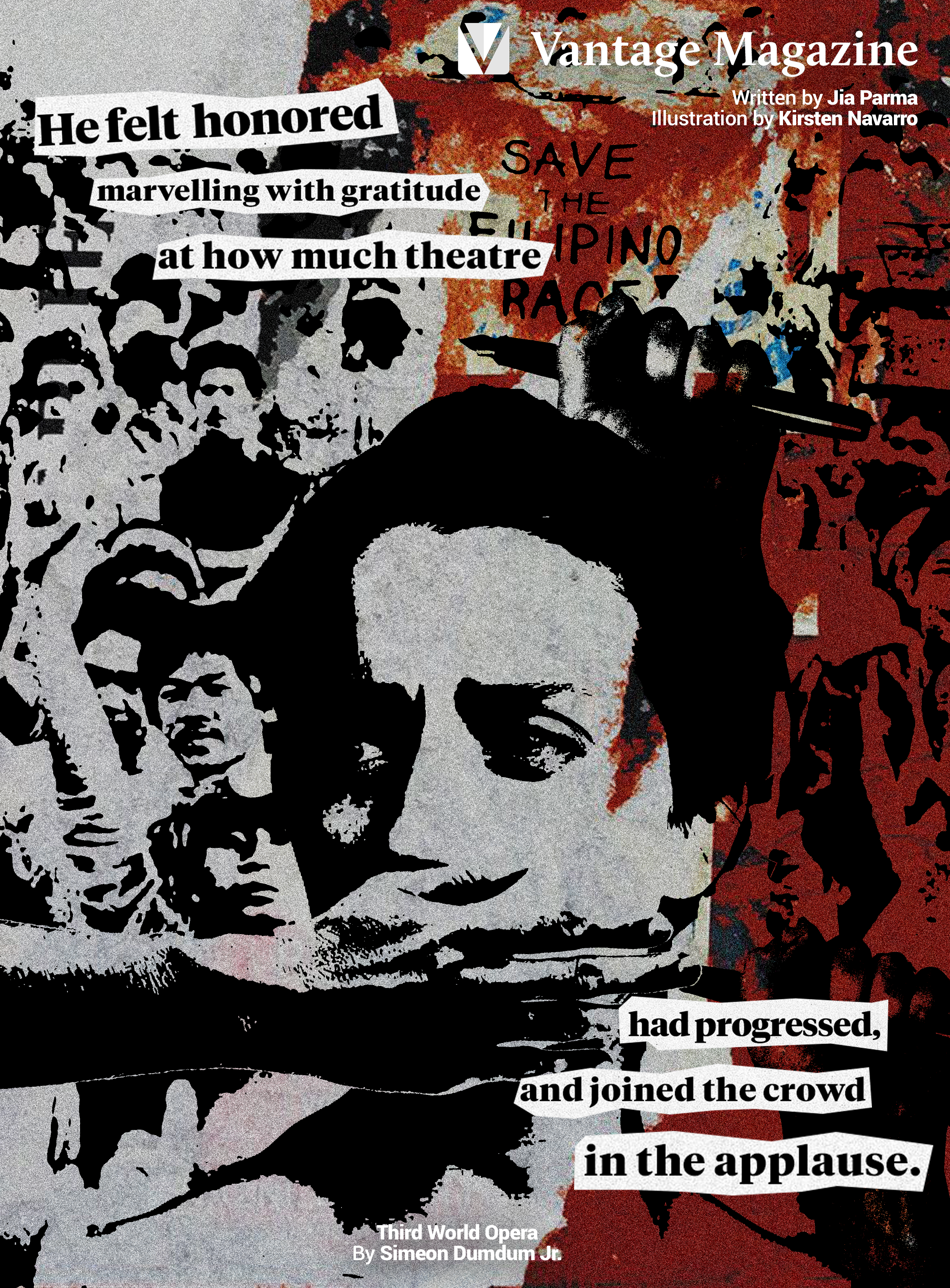

Third World Opera by Simeon Dumdum Jr.

This is another piece directed toward the Marcos dictatorship, now using a carnivalesque approach to reveal the relationship between politics and art—particularly theatrical art. Dumdum Jr. narrates the lead actor’s interaction with the governor:

And so when the actor descended,

In surprising haste,

And planted

A rather realistic kick

In his groin,

He felt honored,

Marveling with gratitude

At how much theatre had progressed,

And joined the crowd

In the applause.

The governor is oblivious to the mockery and disgust that the actor shows. Instead, the politician believes that it’s all part of artistic expression, free from any criticism. This is made apparent by the official’s roaring applause towards the actor. In the context of Martial Law, the Filipino people allude to the actor in the poem, supposedly bound by a script but equally capable of breaking away from the rules and committing an act of defiance against the government.

Extrajudicial Ghazal by Luisa A. Ilgloria

Extrajudicial Ghazal is, as the name suggests, about the ruthless war on drugs that poisoned the nation during President Rodrigo Duterte’s reign. In the poem, the artist Ilgloria does not hold back and blatantly calls out the administration with detailed descriptions that could not be mistaken for anything else. She writes:

The gunmen are anonymous; only eyes show above tightly cinched bandanas.

They pull up on motorcycles, aim, then drive away as the sky darkens.

How does one know who’s truly guilty, who’s accidental casualty?

All are easy targets for the flimsiest charge, as the sky darkens.

The Guerilla Is Like A Poet by Jose Maria Sison

The Guerilla Is Like A Poet is a lyric poem by Jose Maria Sison, former student activist and founder of the Communist Party of the Philippines. He released the poem in 1968, during the presidency of dictator Ferdinand Marcos, Sr., before the declaration of Martial Law. In the 6-stanza piece, Sison relates honing the craft of poetry to that of the intricacies of guerilla warfare. He chooses simple yet elegant words to conjure images of guerillas being in tune with nature, effectively combating their enemies. As Sison puts it:

The guerrilla is like a poet

Enrhymed with nature

The subtle rhythm of the greenery

The inner silence, the outer innocence

The steel tensile in-grace

That ensnares the enemy.

Thirteen Dreams and One Duterte by Eugene Gloria

Thirteen Dreams and One Duterte by Eugene Gloria is a revelatory poem about extrajudicial killings in the Philippines, alluding to the violent war on drugs by narrating thirteen dreams. In an interview, Gloria explained that he chose to narrate the poem as a series of dreams or nightmares because the reality of the extrajudicial killings is astoundingly vile to the point of absurdity. Additionally, while Gloria was born in Manila, he has lived in the US since he was eight years old. Thus, he sees the political unraveling of his motherland as far away and “dreamlike.” He articulates Filipinos’ apathy towards the sheer volume of extrajudicial killings:

[Number7Dream]

The street is so congested

it’s an extrajudicial killing

Manila is so deafening it’s practically soundproof

Examining each of these pieces, it is clear that one must not forget the dialectic relationship between the arts and the political issues of the day. There is a reason that certain writers—literary or otherwise—have been silenced by the most powerful figures throughout Philippine history. Perhaps Jose Rizal was right in saying that the pen is mightier than the sword. Armed with words at our fingertips and fury in our veins, dissent as the people’s tool for accountability must never die.